Woody Allen has always had a particularly deft touch directing women.

Over the course of his career, an astounding twelve actresses have been nominated for thirteen Oscars for appearing in Woody Allen films, and six times they have walked away as winners. Diane Keaton started the streak at the 1978 Academy Awards, where she won Best Actress for Annie Hall. The next year, Maureen Stapleton and Geraldine Page were both nominated—Supporting Actress and Actress, respectively—for Interiors; and Mariel Hemingway was nominated the following year for her supporting turn in Allen’s masterpiece, Manhattan. At the 1987 Oscars, Dianne Wiest won Best Supporting Actress for Hannah and Her Sisters; and Judy Davis gave a volcanic performance, earning a Supporting Actress nomination, in 1992’s Husbands and Wives. Dianne Wiest and Jennifer Tilly both garnered nominations for Supporting Actress, with Wiest earning her second win, for Bullets Over Broadway in 1995. Mira Sorvino took home an improbable Supporting Actress Oscar the next year for Mighty Aphrodite. Samantha Morton earned a Supporting Actress nomination for 1999’s Sweet and Low Down. Penelope Cruz smoldered and erupted her way to a Supporting Actress win in 2009 for Vicky Cristina Barcelona. And then Sally Hawkins and Cate Blanchett were both nominated—Supporting Actress and Actress, respectively—with Blanchett the runaway winner for 2013’s Blue Jasmine.

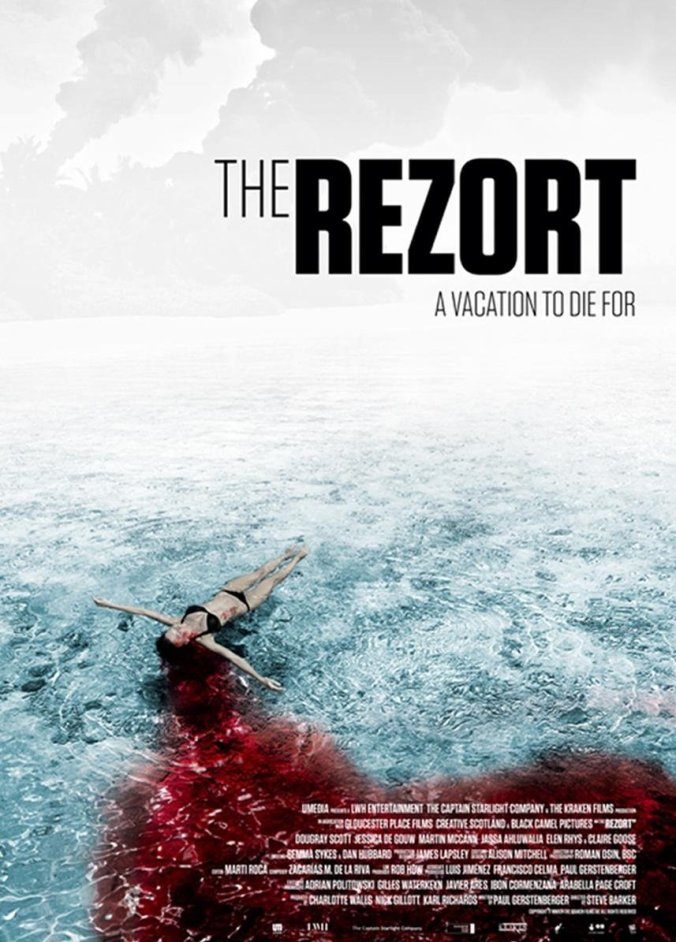

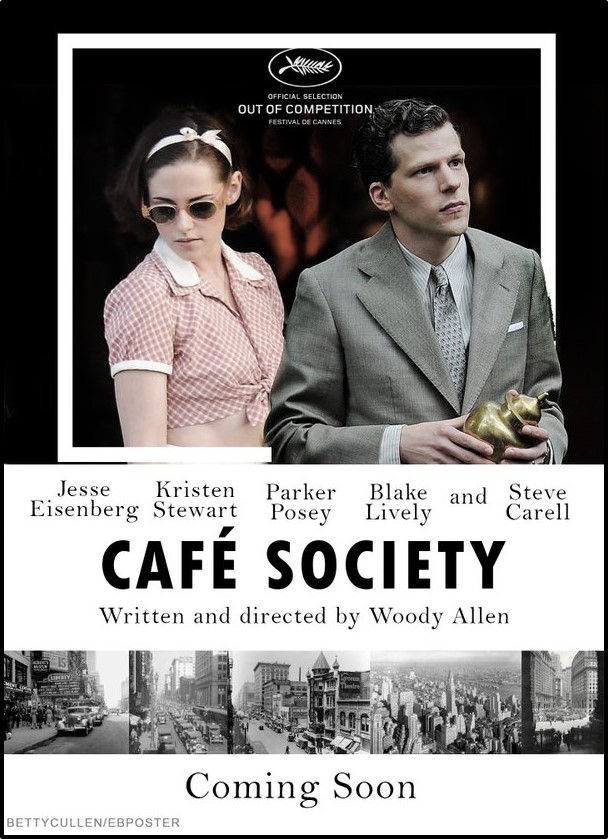

There won’t be any Oscar nominations for Allen’s latest film, Café Society, but once again it is the women who make the film worthwhile, mostly notably Kristen Stewart, who here crackles with intelligence, warmth, and charisma.

Café Society is set in the Hollywood and New York of the 1930’s, a bygone era of glamor, romance, and excitement that has been an obsession of Allen’s for decades. Bobby, a naïve young Bronx boy (Jesse Eisenberg), moves to the West Coast and falls in love with the secretary (Kristen Stewart’s Vonnie) of his uncle, a mogul-ish agent to the stars played by Steve Carell. The relationship gets complicated when Bobby discovers that he is the short leg in an isosceles love triangle, and—heart broken—he packs up and moves back to Manhattan to run a ritzy nightclub with his gangster brother (Corey Stoll).

In recent years, Allen’s movies have taken on the aspect of wistful novellas, often with omniscient, detached narrators doing the heavy lifting not only in terms of moving the plot forward but even in expressing and explaining the emotional state of his characters. In some instances—Vicky Cristina Barcelona and You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger—the device works to varying degrees. In others, like Café Society, it does not. Here, Allen’s voice over recitation of the plot—voiced by Allen himself—strips all the urgency out of the conflicts and interactions of the characters, literally telling us the story while relegating the scenes that the actors are left to play as random vignettes that merely serve to illustrate or punctuate his narration.

But while that narrative device slows and undermines the story, it is Jesse Eisenberg’s limp, tedious performance that ultimately deadens the proceedings entirely.

Eisenberg has given some interesting, effective performances in his career, including his Academy Award nominated turn in The Social Network, but after a solid effort last year in the underrated The End of the Tour, he is having a bad, bad 2016. From his desperately embarrassing Lex Luthor in Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice to the why-in-God’s-name-did-it-get-a-sequel Now You See Me 2, Eisenberg’s effort in Café Society makes it a trifecta of futility.

One common thread that weaves its way through Eisenberg’s 2016 travails is simply that the actor doesn’t fit the role. Eisenberg made his bones playing nerdy, awkward kids in movies like The Squid and the Whale, Roger Dodger, and Adventureland, and so turning in a career-best performance as those characters grown-up and embittered, as he did in The Social Network, made perfect sense. In Café Society, however, while Eisenberg fits as the shy, naïve Bronx kid who opens the story, he is not nearly up to the task of transforming into the confident, charismatic success that he is supposed to be by the end of the film. And willful suspension of disbelief may be the stock-and-trade of the Hollywood dream factory, but asking us to buy that Eisenberg can make both Kristen Stewart and Blake Lively fall in love with him over the course 96 minutes is simply a bridge too far.

Which brings us back to Stewart.

For a young actress, Stewart has had an awfully prolific career so far, including ten films just since 2014 alone. All that experience has helped her tap and tame her natural, raw talent, and the magnetic charm and youthful maturity she puts on display in Café Society suggests an actress ready to come into her own.

While Stewart steals the show as the irresistible Vonnie, Parker Posey in a supporting role and Blake Lively in what is essentially an extended cameo both shine, as well. Posey, especially, gives more personality to what is basically just the sketch outline of a human being than most actors do to fully fleshed out characters, proving once again that one of Allen’s greatest assets as a director is his ability to take a great actress, point her in the right direction, and then just get out of her way.

As for Allen himself, his central preoccupations have changed little over the years, and Café Society reflects his passion for Hollywood of yesteryear, his love of all things New York, and his infatuation with gangsters and other streetwise character who—as he rhapsodized in Manhattan—“know all the angles”. And, of course, even in a trifling work like Café Society, Allen cannot help but ponder the core philosophical quandaries that he returns to time and time and time again in his oeuvre.

As one character opines in Café Society: “Socrates said, ‘The unexamined life is not worth living’. But…the examined one is no bargain.”