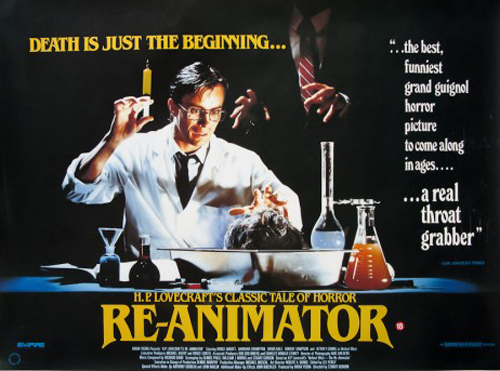

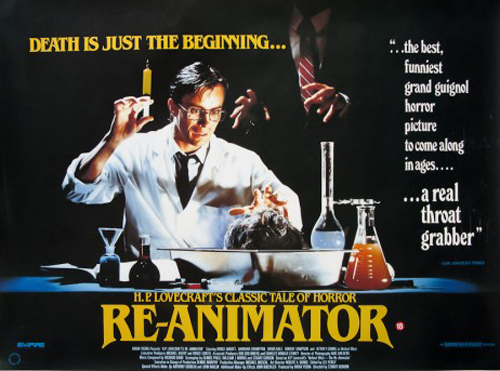

This interview with director Stuart Gordon was conducted in the summer of 1999. The article, originally written for a popular film magazine, ultimately went unpublished and is being circulated now, here, for the first time. At the time of the interview, Gordon had directed a total of ten films in fourteen years—all in the horror, science fiction, and fantasy genres—including his first and most iconic work, the cult horror classic Re-Animator. Since then, he has directed only four more feature films. In the mid-2000’s, though, Gordon enjoyed a bit of a career renaissance as one of Showtime’s Masters of Horror, directing two mini-film episodes of that critically-acclaimed series: Dreams in the Witch-House and The Black Cat. This month, October 2015, Gordon’s Re-Animator celebrates the 30th anniversary of its release.

When Stuart Gordon finally decided to direct a movie, he wanted to make a quick impression. In fact, his approach to his first film might best be summed up by its title character, who—in one pivotal scene—confidently hisses at his rival, “I’ll show you!”

Gordon showed us, alright. His inaugural film, Re-Animator—his confident hiss at the horror genre—is a groundbreaking exercise in over-the-top violence and gore, effective low-budget special effects, and plain old wicked fun.

“One of the things that [producer Brian Yuzna] did was sat me down,” Gordon recalls, “and we screened together just about every horror movie that had been made in the [previous] ten years.”

“The task that he set before us was that we had to somehow out-do these films. We had to come up with a way to go beyond what they had done…be more outrageous or more tasteless or whatever. That was how you made your mark in horror movies, and I think that was good advice.”

It was good advice, indeed. Released in 1985, Re-Animator thrust the first-time director into the cult-film spotlight and helped Stuart Gordon become a minor deity in the world of midnight horror movies.

Re-Animator, a loose adaptation of an H.P. Lovecraft short story, is the tale of Herbert West, an arrogant young medical student who develops a reagent that can re-animate dead tissue. However, when West decides to experiment on human corpses and injects his reagent into various medical school cadavers, he discovers that they are far less enthusiastic about his experiment than he is.

A campy blend of classical horror archetypes mixed liberally with heavy doses of ‘80’s sex, gore, and violence, Gordon’s first film is wildly entertaining and genuinely frightening at times, and it set in motion a film career baptized in crimson red.

Stuart Gordon first developed his love for horror as a child, sneaking out against his parents’ wishes to watch the latest releases at the local theater.

“I’ve always been a fan, ever since my parents forbade me from seeing horror films. So, of course, I had to go see as many as I possibly could,” he laughs.

Gordon speaks reverently of the groundbreaking horror classics of the 1930’s, ‘40’s, and ‘50’s. However, he recalls most fondly the work of horror innovator William Castle, whose sense of showmanship and mastery of the outrageous shaped Gordon’s career both in theater and in film. “There was one [movie] called Macabre,” Gordon remembers, “where you had to sign a life insurance policy before you could get into the theater. And while you were waiting in line to get in, you’d see people being wheeled out on stretchers. It was great theatrics.”

It was those early films, as well as “circuses and other kinds of things that kids get to see when they’re growing up,” that fascinated Gordon and eventually drew him into show business.

“I remember going to see puppet theater and plays,” Gordon recalls. “I found that these things played on in my imagination, and that’s what I like to try to do with my films: get the audience’s imagination working.”

Born in Chicago in 1946, Gordon developed an interest in theater as a student at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. There he wrote and produced a play called The Gameshow, which drew upon the gimmickry and audience interaction that he had admired in William Castle. Gordon and his new-found theater friends went on to produce creative adaptations of Titus Andronicus, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf?, and Hamlet, at one point producing four plays in two months. However, when they produced an adaptation of Peter Pan that included hippies, metaphorical drug trips, and nude dancers, Gordon was arrested for public obscenity and ended up leaving the UW six credits shy of graduation.

Gordon and a number of other members of his student theater company left campus and founded the Organic Theater in Madison. Before long, though, the emerging Chicago theater scene beckoned, the Organic relocated, and Gordon never looked back.

In Chicago, Gordon adapted Animal Farm, which was the first of 40 plays that he would direct during the next 16 years. His initial attempted at horror came when he produced Poe, which Gordon has called “a nightmare version” of Edgar Allan Poe’s life and writings.

Even as he continued to work in theater, though, Hollywood began to take notice of Stuart Gordon.

His play E/R ran for 3 years and was transformed into a successful TV sitcom by Norman Lear. The Organic’s production of David Mamet’s Sexual Perversity in Chicago eventually became the hit film About Last Night. And Chicago’s Public TV station, WTTW, invited Gordon to direct a three-camera production of the Organic’s Bleacher Bums, for which Gordon won an Emmy.

Finally, Gordon decided that it was time to make a movie, but rather than dip his toe carefully into the cinematic waters, he dove into the creative deep-end and generated more than his share of waves.

When Re-Animator opened in 1985, critics did not seem to know how to react. The venerable Janet Maslin warned that the film should “be avoided by anyone not in the mood for a major blood bath.” A more generous Roger Ebert wrote of his fellow Chicagoan’s film that Re-Animator is “a frankly gory horror movie that finds a rhythm and a style that make it work in a cockeyed, offbeat sort of way.” And Pauline Kael effused that it was a “horror-genre parody [at] the top of its class.”

In his own good-natured way, Gordon bristles at the suggestion that Re-Animator is a parody.

“My feeling is that we never intended it to be a parody,” Gordon says in response to Kael’s characterization. “It’s a horror film!”

Not only is Re-Animator a horror film, it may be the most original, definitive horror film of its generation.

The 1980’s was the decade of the stalker and splatter sub-genres, which were born in 1978 with John Carpenter’s Halloween. Through the ‘80’s—and into the ‘90’s—the Halloween sequels, the Friday the 13th films, and the A Nightmare on Elm Street series were the dominant films of the horror genre. Their popularity and box office success set a standard and dictated a formula that hundreds of imitators would follow for decades to come. Even today—in films like Scream, I Know What You Did Last Summer, and their sequels—the formula is not only intact, but celebrated.

“You know, everyone always talks about Scream as being the rebirth of horror,” Gordon says, “but to me Scream is basically just a retread of the old splatter films of the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, just with a hipper sensibility…a sort of self-knowing.”

With Re-Animator, though, Gordon worked outside the new rules and developed his own formula for success. He did, however, recognize the classic conventions common to the best horror films throughout history.

“Well, I’m a huge fan of the old…Universal horror films,” Gordon says, “and then the Hammer films. So those movies were in the back of my mind. I felt like Hammer had gone further than Universal had with the sex and gore. You know, there is always this sort of mix of sex and gore in horror.”

“From the very earliest days of horror, there’s always a connection between sex and death,” Gordon explains. “I think what it is is that sex and death are really two sides of the coin. And I guess what you’d actually say is life and death, really, with sex implying the creation and rebirth and life. And death is the monster.”

“A lot of the old movies,” he continues, “there’s a really strong sexuality that runs through them. One of my favorite scenes is in The Creature from the Black Lagoon, where you see the girl swimming on the surface of the water, and the creature is swimming right below her. And it’s really sexy.”

“In the ‘80’s, with the splatter films, things were getting much more explicit. Things that could only before happen off screen were suddenly happening right in your face. Although, it was mainly in terms of the violence and the gore, and my feeling was let’s go further with the sex, as well.”

Once again, as promised, Gordon went further.

Re-Animator is a monument to Gordon’s ability to mix together a stew of sex, violence, and a third element—humor—to create striking, effective, memorable moments of horror.

In fact, Gordon’s ability to strike that balance was evident right from the start. The very first sequence of Re-Animator demonstrates the dry comic sensibility that would set the tone for the rest of Gordon’s horror career. Then, later in the film, his sense of humor, along with what would become his trademark mix of perverse sex and violence, finds full bloom in what remains one of Gordon’s most memorable film moments.

West’s rival mad scientist, Dr. Hill, has had his head unceremoniously lopped off, only to be re-animated moments later in two separate pieces. While West busies himself with the head, Hill’s headless corpse sneaks up behind him and knocks West unconscious. Despite his designs on word conquest, though, the re-animated Dr. Hill begins his reign of terror with baby steps: by kidnapping a sexy student over whom he has been obsessing. Hill drags her back to the medical school morgue, straps her to an operating table, and—with the decapitated body dutifully holding the severed head in its hands—begins to orally violate her while the girl screams in horror.

In the midst of this disturbing assault, West appears out of nowhere and dead-pans: “I must say, Dr. Hill, I’m very disappointed in you. You steal the secret of life and death, and here you are trysting with a bubble-headed coed. You’re not even a second rate scientist.”

Like his manipulation of sex and violence, Gordon—who also co-wrote Re-Animator—uses humor intentionally in his horror films, calling those moments “safety valves” that allow his audience to blow off tension before he plunges them back into the horror.

“When you have a horror movie audience,” Gordon explains, “you have an audience that really wants to laugh. I think that the reason is that laughter is an antidote for fear.”

He also recognizes that, to an extent, horror and humor go hand-in-hand.

“Hitchcock used to say that comedy and horror were basically the same emotion,” he says, “which I couldn’t quite understand, but I can sort of get a sense of it. Telling a joke is kind of like scaring somebody, in a way: there’s a set-up—a build-up to something—and then a surprise.”

Horror, he says, follows the same basic formula.

However, Gordon also recognizes that too much humor—or the wrong kind—can dilute the horror and alienate his audience.

“The fans take this stuff very seriously, and so does anyone who really loves [horror], and they don’t want someone mocking it,” he says. “But I think that the fans do like it when there’s a sense of humor that’s part of the process…but that’s not at the expense of the situations or the characters.”

“I think that there has to be a respect for the genre there,” Gordon concludes.

Not only has Gordon demonstrated a respect for the genre over the course of his film career, he has demonstrated a mastery of it, as well. That success comes in part from an evolving understanding of what makes horror work.

“I think that one of the things I’ve been learning,” Gordon explains, “is that horror is slow. In a sense, the slower it is, the better it is. It’s sort of the opposite of action, where you have a lot of quick cutting. But in horror, what really kind of freaks out an audience is the expectation of what they’re about to see.”

“It’s sort of like the unmasking of the monster in Phantom. No matter how great your makeup is, as soon as you see that whatever it is, it’s sort of like, OK, I can deal with this. But it’s not knowing what it is that is really what gets to you. And, again, it’s that you put the audience’s imagination to work…and they imagine things that are much more upsetting than anything that you can create.”

“The unknown is always more scary than the tangible or the known.”

Gordon continued to explore the unknown in his next film, From Beyond, in 1986. Again, based on H.P. Lovecraft’s work, Gordon’s second film strove for the same blend of sex, violence, and humor that made Re-Animator such an instant and enduring horror classic. His success the second time around was more moderate, but he maintained his reputation as a director who would push the edge of the envelope, and From Beyond produced a number of very effective horror moments.

“What we tried to do with From Beyond,” Gordon says, “was to have [the monster] constantly metamorphosing, so that you never were going to get the ultimate horror. You knew it was going to be something different each time.”

From there, Gordon went on to produce seven more films in the horror and science fiction genres, with varying degrees of success: Dolls (1986), The Pit and the Pendulum (1990), Daughter of Darkness (1990), Robot Jox (1991), The Fortress (1993), Castle Freak (1995), and Star Truckers (1997). At the same time, he wrote the screenplays for the films Body Snatchers (1993) and The Dentist (1996), and he received story credits for The Progeny (1997) and the box office hit Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989).

Like Re-Animator, which revived a nearly defunct horror archetype—the mad scientist—Gordon’s most recent horror film, Castle Freak, reaches back into the genre’s classic past to explore another nearly-forgotten horror subgenre: terror in a Gothic castle.

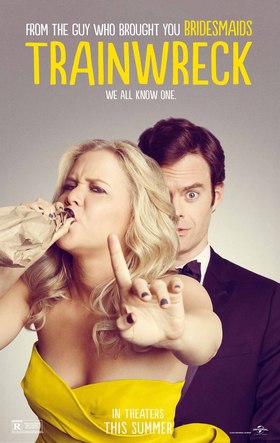

However, Gordon’s latest film, The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, takes the director in an entirely new direction. A direct-to-video release, The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit is a family-friendly comedy about the hopes and ambitions of five friends from the barrios of South Central L.A. Gordon had produced the Ray Bradbury play twenty years before on the stage, and when he decided to take a break from horror, The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit seemed to be the perfect vehicle for him. It gave him and the other people involved in the film—like veteran actor Edward James Olmos—a chance to spread their wings and try something new.

“Originally, I was going to cast [Olmos] in a different part,” Gordon confesses, “and he said, ‘I’d be happy to play it. I like this movie. I want to be in it. But I’d much rather play Vamenos,’” the broad comic role. “And I was trying to think of a tactful way of saying this to him, but finally just came out and said, ‘Well, Eddie, can you be funny?’ And he then proceeded to show me. He went through the whole script with me, and I was on the floor. He was so funny!”

“You know, Hollywood has a tendency to want to typecast you,” Gordon continues. “Because I did Re-Animator as my first film, that’s sort of all they want me to do: horror films. Eddie Olmos’ first movie, I think was Zoot Suit, and he was so stiff in that, everyone just sort of saw him as a serious actor. But he’s incredibly versatile. This movie was a chance for all of us to sort of do something different.”

In addition to Gordon and Olmos, the “all” that the director refers to is a terrific ensemble cast, including Joe Mantegna, Esai Morales, Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez, and Gregory Sierra, as well as comedy veterans Sid Caeser and Howard Morris.

Gordon credits his theater background with teaching him how to get the most out of actors.

“You know, I spent 15 years directing theater,” Gordon notes, “and it made me really love being in the company of actors. It’s great fun, and I think it’s one of the things that unfortunately is not taught in film schools. Film students learn all sort of technical know-how, but the actual working with the actors is something they have to pick up on their own. It’s too bad, because I think that’s where the heart of it all is.”

That love of actors has compelled Gordon to work with many of the same actors from film to film.

“When I did theater,” Gordon recalls, “you spend the whole time you’re working with somebody just getting to know them, and you really don’t start doing your best work until you’re working on your second or third piece with the same person. And I think movies even more so. Everyone just sort of shows up on the first day of shooting, and you kind of hope it’s going to work out. Everyone has a different way of working, a different method, different things that they like to do and that they don’t like to do…and it takes a long time to sort of get on the same wavelength. I think that that’s where the key is. When you find people who you can communicate with and whose work you like and they like yours…you should hang onto those people.”

Gordon also plans to hang onto the genre that established him as a film director. Although The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit provided a nice change of pace for him, Gordon plans to jump back into the horror genre with his next film.

“I think that the next piece that I’m going to do is going to be a horror film,” Gordon predicts. “I’m working on a couple of things, and both of them are very intense horror films.”

However, even as he prepares to return to his roots, Gordon senses a change on the horizon for the horror genre, which he sees as the natural order of things.

“I always think about the TV series The Munsters,” Gordon says. “You’ve got the Frankenstein makeup, and it’s funny. Well, when that makeup originally premiered, supposedly women were having miscarriages and stuff because it was so horrifying.”

“I think it’s part of what happens with horror,” Gordon explains. “Each generation has to reinvent it for itself. You know, the things that scared our parents we think of as sort of corny and quaint, and our kids will think that the stuff that scared us is equally ridiculous.”

The director sees that transition happening already, with the stalker/splatter films beginning to parody themselves.

“Scream in a sense does and doesn’t,” Gordon says. “It still is going for genuine scares. Wes Craven, I think, is a great filmmaker. So it’s not parodying it, exactly. But I do think that some of the more recent [series], like A Nightmare on Elm Street, for example [are]. Freddy Krueger is no longer scary. He’s become a comedian.”

“I think it is definitely the end of the splatter film,” he continues. “That’s pretty much over. Peter Jackson’s movie—here it was called Dead Alive, in Europe it’s called Braindead—just went so overboard with the splatter that it really became just like a Roadrunner cartoon. It wasn’t scary. It was funny.”

“So, I think audiences get used to anything after a while, so you just have to keep coming up with new ways to scare people.”

Those new ways, Gordon thinks, are coming from outside the Hollywood mainstream. While Hollywood continues to squeeze whatever life is left out of the stalker/splatter subgenres, Gordon sees the best horror coming from elsewhere, singling out Dario Argento for his highest praise.

“One of Dario Argento’s latest movies,” Gordon says, “which was just great, great, was called The Stendhal Syndrome. Unfortunately, it never played in the U.S. I saw it at a film festival, and it really freaked me out. It was really scary, and he was just doing some brilliant stuff with that movie.”

“Apparently, Stendhal had some sort of mental illness in which—when he was overstimulated—it was literally too much for him and he would just faint. There’s a story about him going to an art museum and seeing the paintings, and the paintings were just too much for him. And that’s sort of the basic idea of Argento’s film. He even has a scene just like that at the beginning of the movie, in which he has the heroine at an art gallery and has the painting sort of coming to life.”

“It’s really just masterful, and in a way, it’s sort of an allusion to the movies…the idea that movies sometimes get to be too much for you. His film certainly does.”

Although he remains mum on the specifics of his upcoming projects, Gordon indicates that he has always wanted to adapt Stephen King, and he plans to return to the works of Poe and Lovecraft at some point.

“Lovecraft has got so many great stories that have never been adapted to the screen,” Gordon beams. “I feel like it’s kind of like a treasure trove of wonderful things, especially for those who love low-budget, visceral horror.”

And with the promise of a return to horror next on his agenda, the midnight movie crowd can hardly wait to find out what Gordon plans to show us next.