With 2015 now officially in the rear view mirror, it turns out to have been a sneaky-good year at the movies. Despite The Force Awakens pretty much sucking all of the oxygen out of the cinema universe this year—even before its mega-debut in December—2015 gave us some quality films throughout the year.

The following Top 10 represents, in no particular order (well, in alphabetical order, in fact), my own personal “best of” list for 2015. Many of these will be found on other critics’ best of lists, and many of them will be awards contenders in the coming months. Some, however, simply struck a nerve with this particular critic and found their way onto the list. If you think there is movie missing that should be on the list, it’s entirely possible that I didn’t get to see it this year…or that it simply didn’t make my cut. That shouldn’t stop you from putting it on your own list, however!

The Big Short

Corruption. Stupidity. Greed. Co-writer and director Adam McKay posits in The Big Short that it was the confluence of those particular sins that led to the global financial disaster in the first decade of this century; and he presents the lead-up to that meltdown through the stories of three teams of financial professionals who saw it coming and set out to profit from it. For a story that unfolds primarily through phone calls, in Wall Street meeting rooms, and around the analysis of mortgage documents and investment prospectuses, The Big Short bristles with creativity and energy. Not to mention moral outrage. Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, Christian Bale, and Brad Pitt headline the cast—with Carell and Bale delivering the most interesting takes on their real-life characters—but this is a movie that succeeds because of the collective. Lead actors and the supporting cast alike rivet from start to finish. There is nothing on Adam McKay’s robust comedy resume (the Anchor Man movies, Talladega Nights, Step Brothers, and more) to suggest that he could deliver a film of such incisive wit and moral weight, but with The Big Short he may have written and directed the best film of the year.

Ex Machina

It’s no coincidence that Oscar Isaac appears in three of the films on this particular “best of” list. In 2015, he confidently staked his claim as one of the finest actors of his generation. In Ex Machina, he portrays a reclusive tech genius who just may have produced the world’s first sentient machine. He invites a star employee of his tech empire to his secluded island estate and introduces him to Ava (or is it Eve?), his latest version of sexualized artificial intelligence. Alicia Vikander slyly portrays Eva as Woman.0, and by the end of the movie we hear her roar. Ex Machina is a creepy, slow burn, and it lingers long after the final credits roll.

It Follows

The most interesting and understated horror movie of the year was It Follows. Part supernatural horror and part surprisingly complex morality tale, It Follows both subverts and validates the genre’s conventions regarding sex, death, and punishment. After a young girl is seduced into a sexual encounter with a mysterious new boyfriend, she finds herself haunted and pursued by an evil demon that inexorably stalks her no matter where she tries to run or hide. She can’t destroy it, and she can’t escape it. Her only hope of surviving is to have sex with another person, which will then pass the curse from her to her partner. What could have been a clumsy, typical teen blood fest is instead, in the hands of writer/director David Robert Mitchell, a masterclass in mounting suspense and hair-raising imagery. Though it rattles off the rails a bit in its closing stages, the difficulties with its resolution are not enough to undermine the style and power woven into the rest of the film.

Love & Mercy

Love & Mercy alternates back and forth between the two periods in life of Brian Wilson, the creative genius behind The Beach Boys. Paul Dano portrays a younger, faltering Wilson, and John Cusack fills the role of an older, emotionally broken Wilson. The unconventional approach—two different adult actors playing the same character at different points of his life—works in unexpected and riveting ways. After two decades of struggle with debilitating mental illness, drug abuse, and family turmoil, the fragile, dependent Wilson of the 1980’s indeed seems to have been a completely different man than the energetic, dynamic Wilson of the Pet Sounds era. Dano and Cusack famously did not coordinate their takes on Wilson and barely even met before or during the film’s production, and as a result their individual portrayals of the man are crafted and shaded in their own unique ways. And both deliver, as does a stellar Elizabeth Banks in a supporting role. Read Madison Film Guy’s full review here.

Mistress America

Indie actress-cum-screenwriter Greta Gerwig has emerged in recent years as a truly idiosyncratic cinematic voice, with her latest film, Mistress America, a minor-though-charming addition to her growing and impressive filmography. Mistress America, which Gerwig stars in, co-produced, and co-wrote with director and best beau Noah Baumbach, is an unexpansive meditation on loneliness, narcissism, and the cult of (failed) ambition. And, like much of Gerwig’s most personal work to date, it delights in the struggle of a generation desperate to find its place as it comes to terms with the twilight of youth and the dawn of adulthood. Gerwig’s cinematic baptism has come at the altar of filmmakers like Whit Stillman and Baumbach himself, and it shows in her scripting of Mistress America. And that’s not a bad thing. Though less self-conscious—but dramatically warmer—than movies like Metropolitan or Damsels in Distress (which Gerwig starred in, as well), Gerwig the writer shares a talky, erudite style with Stillman and Baumbach. But her earthy, human moments are significantly more impactful and resonant. Read Madison Film Guy’s full review here.

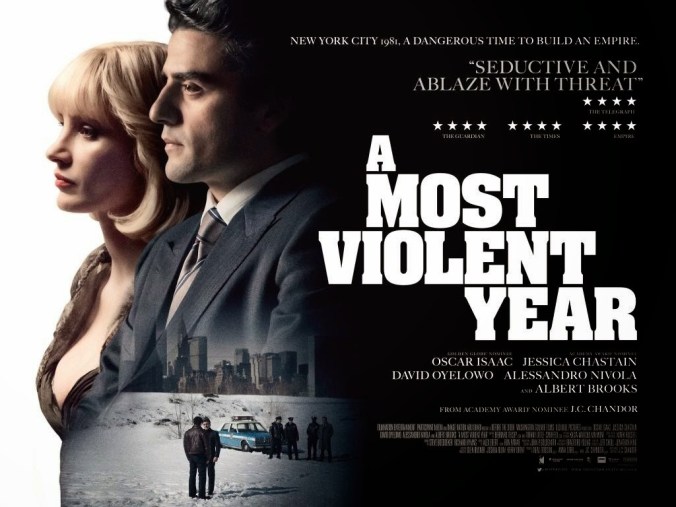

A Most Violent Year

Sidney Lumet was a titan of 1970’s filmmaking, imbuing his films with rich complexity and indelible style. Though his career spanned more than 50 years, in that one decade alone, Lumet gave us such signature films as Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Network, among many others. Lumet died in 2011, but director J.C. Chandor seems to have been channeling the great man’s spirit in A Most Violent Year. Technically released (limited) on December 31 of 2014, I’m going to count A Most Violent Year on this list, because it didn’t really hit theaters until the early part of 2015. And it would be a shame not to give it its due. With the look and feel of a 1970’s gangster film but the pacing of a deeply personal drama, the film tells the story of an ambitious Latino immigrant attempting to protect his business, his family, and his honor during the violence of 1981 New York City. Starring Oscar Isaac and Jessica Chastain, A Most Violent Year never combusts, but it smolders with quiet, restrained intensity in every frame.

Spotlight

An example of your classic late-year prestige picture, Spotlight checks off all the right boxes to make it a serious Oscar contender: great ensemble cast, important subject, quality script and direction, and pretty much everyone involved putting their best foot forward. Directed by Tom McCarthy, Spotlight chronicles the months-long quest by the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” investigative team to draw back the curtain on Boston’s massive clergy-abuse scandal in the early 2000’s. The film functions not only as a scathing indictment of the role of the Catholic church in covering up and perpetuating the abuse, but also as a testament to the importance of a strong, healthy free press in exposing and challenging the wrongdoing of the most powerful institutions in society.

Star Wars: The Force Awakens

The story and thematic parallels between this film and the original Star Wars have been much remarked upon in recent weeks and in some quarters roundly criticized, but for the most part, The Force Awakens actually delivers on the year-long hype and decades-long anticipation that ushered in its arrival. “It’s true,” Harrison Ford’s Han Solo assures us at one point. “All of it. The Dark Side, the Jedi. They’re real.” That’s how we felt watching Star Wars for the first time nearly 40 years ago, and that’s how this movie makes us feel once again. The Force Awakens is the movie we’ve been waiting for since 1983, and you come away from it reassured of one thing: The Force will be with you. Always. Read Madison Film Guy’s full review here.

Steve Jobs

Deconstructing Apple co-founder Steve Jobs through an interesting, practically theatrical 3-act structure, writer Aaron Sorkin and director Danny Boyle paint a portrait of a self-righteous, morally fallible genius who is wrong more than he is right. But when he’s right–whoa!–he’s really right. Sorkin’s crackling script, Kate Winslet’s Oscar-worthy second banana, and a host of solid supporting turns (Seth Rogan and Jeff Daniels, among them) take a backseat to Michael Fassbender’s intense, penetrating portrayal of Jobs himself. Fassbender has been putting some riveting work on film the last several years, and here he is alternatively seductive and repugnant. In berating loyal employee Andy Hertzfeld before the launch of the Apple Macintosh computer, Fassbender’s Jobs hisses, “You had three weeks. The universe was created in a third of that time.” Without skipping a beat, Hertzfeld replies, “Well, someday you’ll have to tell us how you did it.” And that’s Steve Jobs in a nutshell.

What We Do in the Shadows

Released in the United States in early 2015, What We Do in the Shadows succeeds due in large part to its palpable love and appreciation of the horror classics. Its humor may be modern, but its roots and inspiration burrow through more than a century of classic horror cinema. More Young Frankenstein than Scary Movie 5, Shadows’ affectionate take on the horror comedy offers equal parts satire and homage, with dashes of genuine melancholy and dread thrown in for good measure. It’s an instant classic. Read Madison Film Guy’s full review here.

There have been a number of movies in the last year that have been, despite their excellence, particularly hard to watch. Selma comes to mind, as it was difficult not to juxtapose yesterday’s historic struggle for voting rights for African Americans with today’s dispiriting attempts to roll those same rights back and disenfranchise those same people. Suffragette elicited a similar reaction, presenting a striking dramatization of the struggle of women to achieve social justice and independence, released during this year in which women’s rights are under cynical and flagrant attack once again.

There have been a number of movies in the last year that have been, despite their excellence, particularly hard to watch. Selma comes to mind, as it was difficult not to juxtapose yesterday’s historic struggle for voting rights for African Americans with today’s dispiriting attempts to roll those same rights back and disenfranchise those same people. Suffragette elicited a similar reaction, presenting a striking dramatization of the struggle of women to achieve social justice and independence, released during this year in which women’s rights are under cynical and flagrant attack once again.